Become your own meteorologist with Wilderness Weather Fundamentals from Outside Learn. Recognize storm clouds, measure changes in pressure, stay safe from lightning and other dangerous weather, and more. Outside+ members can start learning right now.

Watch: Learn to predict the weather with Wilderness Weather Fundamentals from Outside Learn.

What Causes Storms?

All weather activity is driven by atmospheric lift, or the vertical movement of air. As air rises, it cools, causing water vapor to condense and clouds to form. With enough lift, you get precipitation. Faster lift causes more-dramatic weather changes.

Air doesn’t lift itself. Four factors drive lift: fronts, low-pressure systems, mountains (which cause what’s known as orographic lift), and convection (when the sun warms the earth’s surface).

Fronts

A cold front is a boundary of cooler air pushing up warmer air ahead of it. Clouds and precipitation lie along and just ahead of a cold front. Cold fronts cause dramatic uplift and are often responsible for severe weather.

A warm front is a boundary of warmer air that rides up over colder air. Warm fronts gradually slope upward from the ground and are often preceded by clouds by several hundred miles. Typically, steady precipitation is found ahead of a warm front.

Pressure

Atmospheric pressure (or barometric pressure) is a useful predictor for weather conditions. High-pressure systems bring fair weather with few clouds. Low-pressure systems, on the other hand, cause air to rise, bringing clouds, precipitation, and wind.

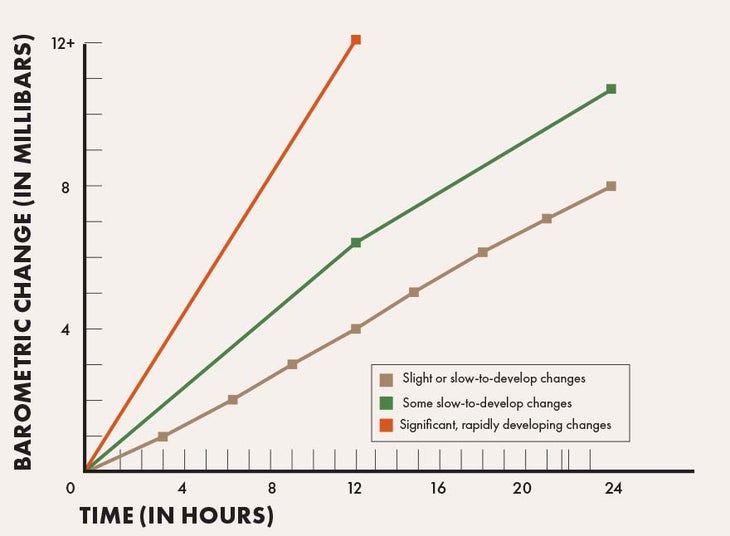

Observing pressure changes can help you predict the weather, as long you don’t change your altitude much (pressure decreases with elevation). Sports watches with barometers are great tools for hiker-forecasters. This graph shows you how to interpret fluctuations in pressure:

Temperature and pressure are directly related. Large changes in pressure are often driven by significant temperature changes. A drop in pressure is a good indicator of cold air coming in, and a rise in pressure is a good indicator of warm air on the way. Check your barometer in the morning and a few times throughout the day. Pressure changes over six to 12 hours can help you predict short-term temperature swings. Significant pressure changes mean you can expect the weather to change.

Master the Lightning Crouch

No hiker wants to get caught in a storm. But if you can’t find shelter, follow these steps to lessen the chances of injury.

Around 50 people die in the U.S. from lightning strikes each year, says Alex Anderson-Frey, assistant professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Washington. Don’t be one of them—check the forecast ahead of time and stay off summits when storms are near. If you find yourself caught in a storm, assume the lightning crouch: “Keeping your feet together and crouching low to the ground will reduce your odds of being struck and reduce the length of the path the electricity will take through your body if you are struck,” she says. With your heels together, a strike will travel through your foot and pass into your next foot via your touching heels, instead of traveling through your entire body. Remain crouching until the threat has passed. “Lightning is still potentially a danger up to half an hour after you hear the last rumble of thunder,” says Anderson-Frey.

Clouds

Clouds can tell you what the wind is doing in the upper parts of the atmosphere, and they show what direction the weather is coming from. Clouds can also reveal how stable or unstable the atmosphere is and how far away a storm may be.

There are two basic cloud types:

Stratus clouds are flat, lower to the ground, and indicative of stabler conditions.

Cumulus clouds are puffy, tall, and indicative of unstable or stormy conditions.

Observations that hint at the forecast:

Cloud-base heights: Descending cloud bases indicate deteriorating conditions; rising clouds indicate improvement.

Cloud movement: This can tell you about wind patterns up high and show where a storm is coming from.

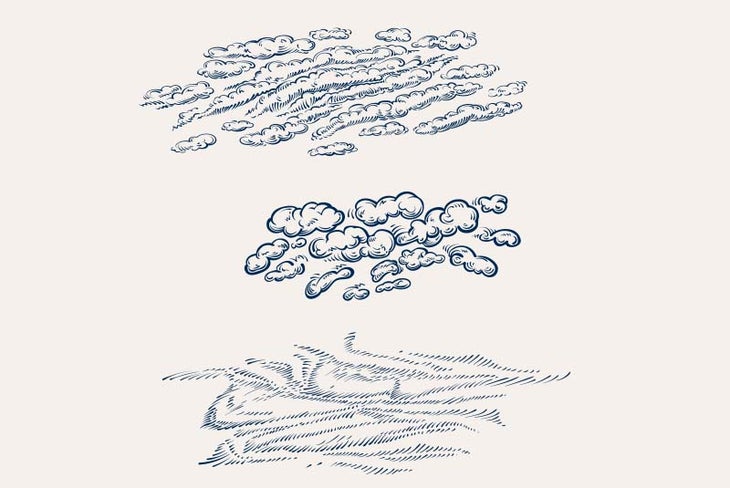

High-Level Clouds (16,000 to 40,000 feet)

Cirrocumulus: These puffy clouds form a broken layer that can resemble sheep fleece or fish scales, and they indicate increasing moisture and an atmosphere that is becoming unstable. They can also signal an approaching cold front.

Cirrostratus: This thin cloud layer forms a halo around the sun and is made of ice crystals; when the sky is overcast like this, expect precipitation in the next 24 hours.

Cirrus: These high, wispy clouds tend to precede warm fronts.

Mid-Level Clouds (6,000 to 16,000 feet)

Altocumulus: Often appearing in rows, altocumulus clouds are gray, medium-size puffs; they can indicate rain or snow at high elevations or a general trend toward unstable weather.

Altostratus: A gray, uniform sheet over the sky indicates impending rain.

Lenticular: These flying-saucer-shape clouds can be seen capping mountaintops and indicate the presence of very strong winds near the peaks.

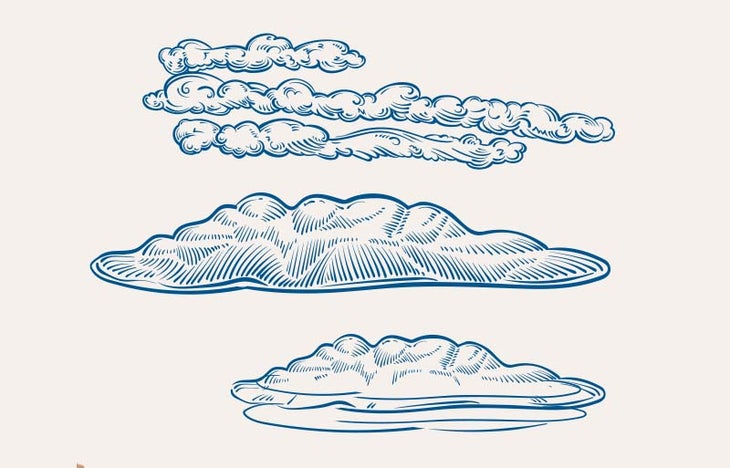

Low-Level Clouds (below 6,000 feet)

Cumulus: These familiar white and puffy clouds can grow very tall or develop into cumulonimbus, and they may produce a shower or thunderstorm. Cumulus typically forms in a line near the leading edge of a cold front.

Nimbostratus: These amorphous, dark gray clouds produce rain or snow.

Stratocumulus: These clouds are dark and rounded and indicate the possibility of precipitation.

Stratus: The thicker these low, foggy cloud layers are, the less precipitation they’ll produce. Thinner stratus layers can bring drizzle.

Clouds that Occur at Any Level

Cumulonimbus: These clouds have dark bases and tall columns that may have an anvil shape at the top. They produce full-fledged thunderstorms with lightning, hail, and strong winds. Watch out!

Making a Field Forecast: Observe Everything

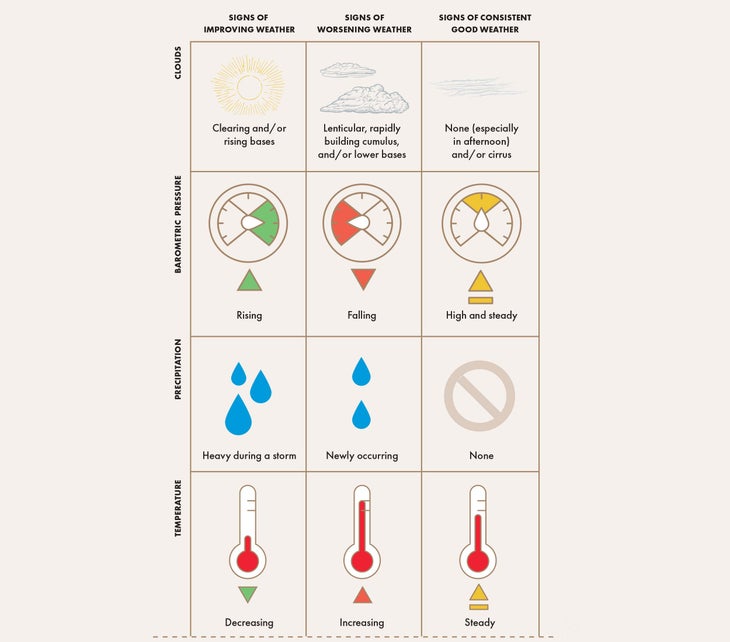

The weather will do one of three things: stay the same, deteriorate, or improve. Here’s how to predict what’s on the horizon.

In-the-Field Forecasting

Once you head into the backcountry, you leave the resources of online weather forecasts and weather apps behind. In the field, you won’t be able to make predictions very far into the future (12 to 24 hours is a reasonable goal), so it’s imperative to constantly look for changes or trends—even when the weather is good.

You’re Doing It Wrong: Estimating Wind Speed

It’s easy to tell the difference between a breeze and a gale. But when it comes to putting a number on it, you’re probably overestimating.

Ever returned from a trip and told your friends, “The winds must have been 60 miles an hour up on that ridge”? Whether you meant to or not, you were probably exaggerating. “In most cases, as you climb higher in elevation, wind speed, in general, will climb higher as well,” says Ryan Knapp, weather observer and meteorologist at Mount Washington Observatory in New Hampshire. But keep in mind: wind speed and force are two different elements. “As you double wind speed, you quadruple the force—and increase its power eightfold.” Hikers often overestimate wind speed, since it feels much stronger than it actually is. “Most people are familiar with what a five-to-ten-mile-per-hour wind feels like, as this is common where they live,” says Knapp. “But start climbing in elevation and they might feel 30-, 40-, or 50-plus mph, and those winds will feel exponentially higher than what they might have experienced prior.” Use these benchmarks to estimate better:

20 mph: Large tree branches sway and small waves form on water

35 mph: Walking into the wind becomes more difficult, and large trees bend

50 mph: Branches break, and it’s very difficult to stand or walk

65+ mph: Large trees become uprooted and trucks can be blown over

Ready to discover your own dormant capabilities at Outside Learn? Join Outside+ today.

The post Stay Safe by Learning to Predict the Weather in the Backcountry appeared first on Outside Online.

by cobrien via Outside Online

Comments