In 2015, Victor Temprano protested a pipeline project in British Columbia. Standing alongside Indigenous peoples who steward that land, Temprano asked himself whose lands the project would impact. He started mapping the pipeline paths, oil spills, and protests across Canada.

Temprano’s quest to close the loop on that question opened the floodgates. His work of mapping Indigenous relations to land expanded, leading him to create Native Land Digital in 2018. While Temprano is a settler from Okanagan territory with no previous experience in mapmaking, Native Land Digital has blossomed into an Indigenous-led not-for-profit organization with a digital map depicting Indigenous territories, treaties, and languages, all presented on a global scale. In fact, its map now serves as the de facto resource for understanding Indigenous relationships to land.

“It’s an educational tool for people to know that there’s a history in a place that is thousands and thousands of years older than European history,” says Christine McRae, Native Land Digital’s executive director who belongs to the Crane clan of the Madawaska River Algonquin people.

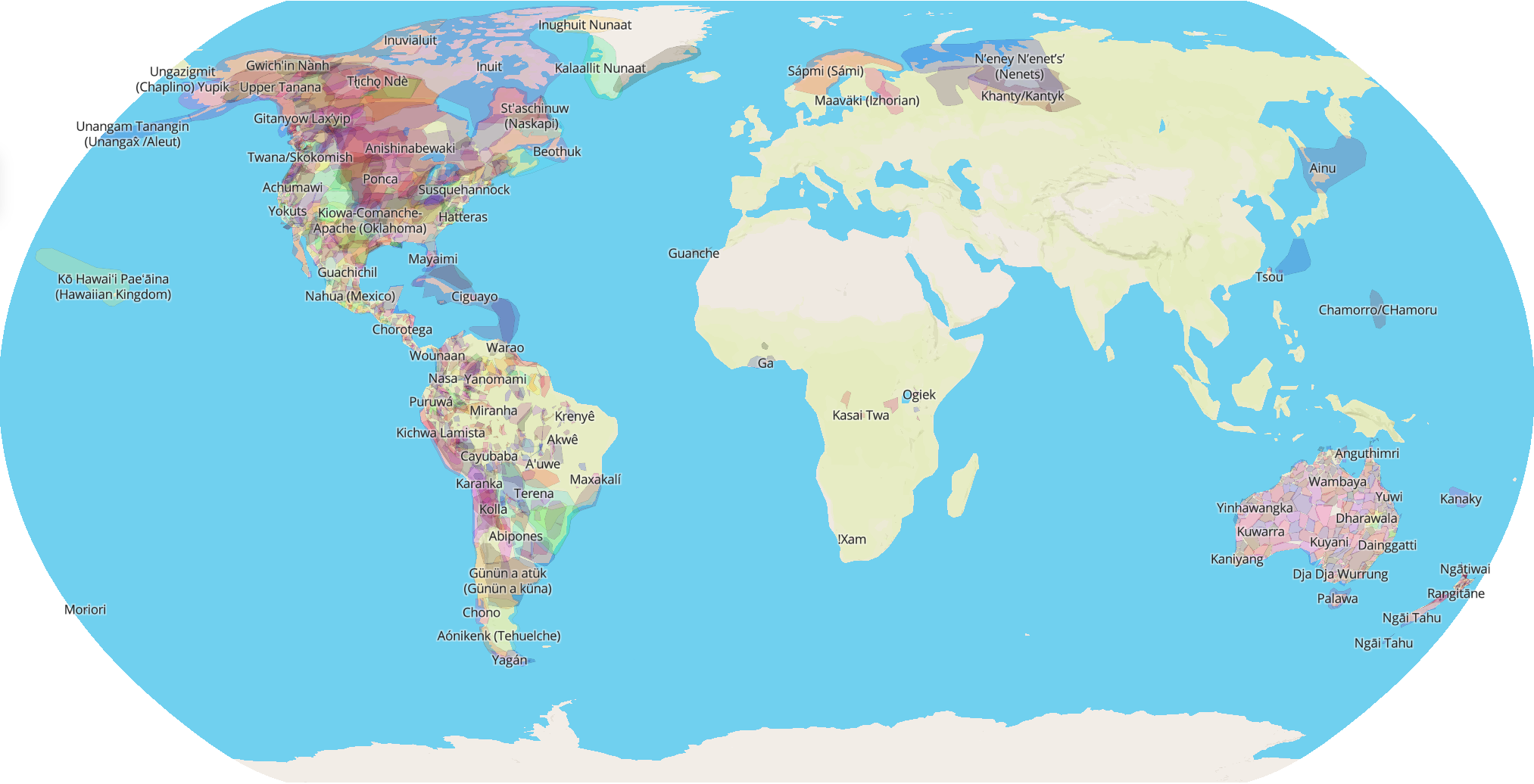

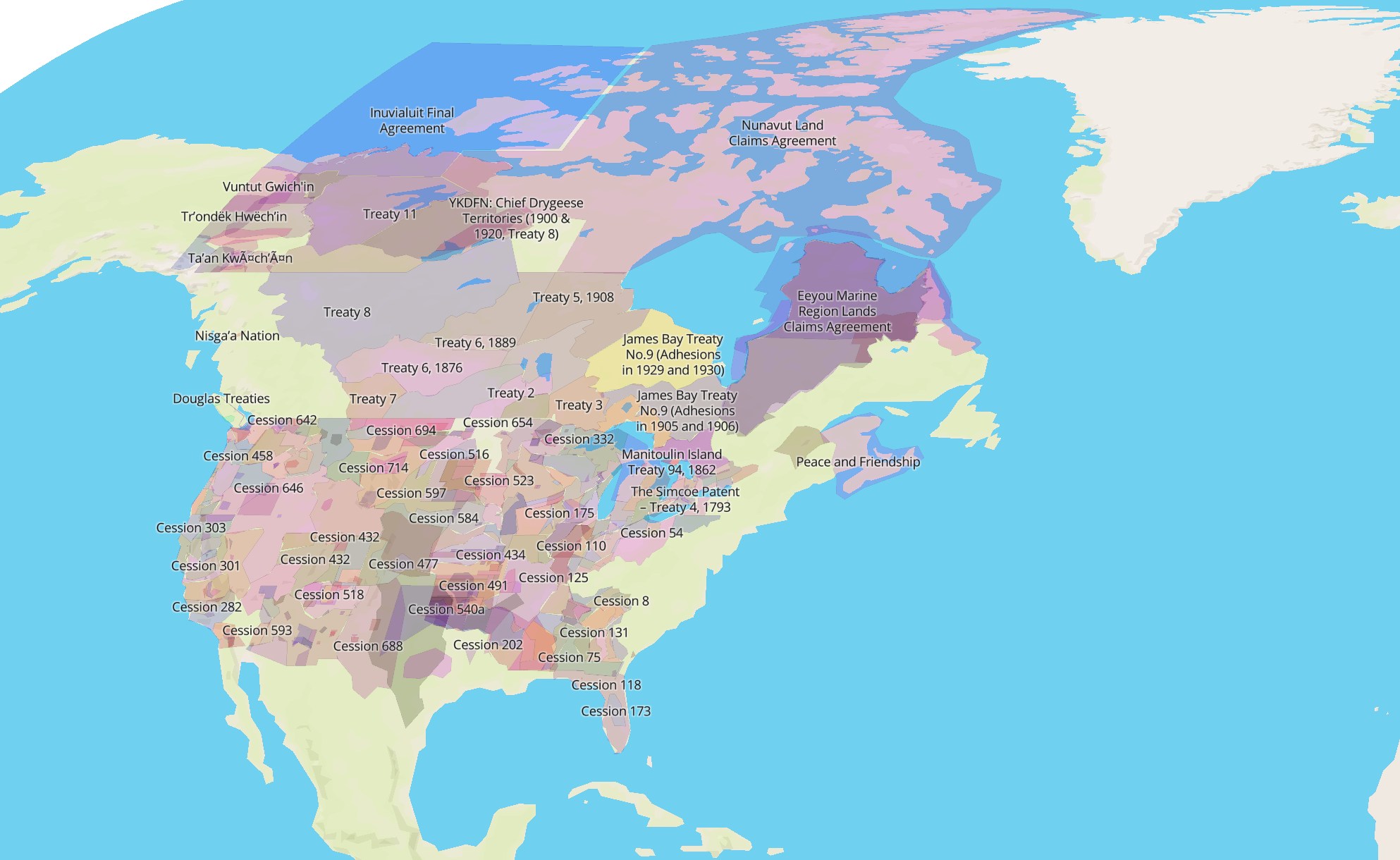

The interactive map contains a trove of crowdsourced information about Indigenous peoples all over the world, including Indigenous territories, languages, and treaties across every continent. Native Land Digital receives over 700,000 visits on holidays like Thanksgiving, National Indigenous Peoples’ Day, and Canada Day, and it inspires complicated, needed discussions.

By prioritizing Indigenous knowledge and connections to land on its digital map, Native Land Digital invites us to ask: What does it mean to attach a name to a landscape? While that answer remains relatively straightforward from a Western-colonizer perspective, that’s not the case from an Indigenous one, as Temprano has learned.

Starting from Scratch

When you open the Native Land map on Native Land Digital’s website, on the Gaia GPS website, or in the Gaia GPS app, it’s immediately obvious that it looks very little like ubiquitous Western maps. The same landmasses appear, yet they’re covered in overlapping shapes rather than rigid country and state lines.

You can choose from three maps: Indigenous territories, languages, and treaties. While you can turn Western boundary markers on, that’s not the default setting. Instead of a jigsaw puzzle, you see a watercolor painting.

“We don’t include those [Western] boundaries on the map on purpose, so that we can understand that the colonial way of understanding the world is not the only way,” McRae says. “There is a much older understanding of land, territories, waterways, and so on.”

Maps are such ingrained fixtures of Western culture that it’s easy to think of them as immutable objects of truth. But in truth, maps come closer to paintings than photographs. Field measurements contain errors in accuracy and precision. And no map can depict all physical, biological, and cultural features for even the smallest area.

Beyond inaccuracies, maps represent one viewpoint—that of the mapmaker or their patron. A map can display merely a few selected features, usually portrayed in highly symbolic styles and according to some kind of classification scheme. All maps are estimations, generalizations, and interpretations of true geographic conditions. What a cartographer chooses to include or leave out, even boundary lines themselves, reflect deeply rooted norms and a subjective valuation of both what is important and what is reality.

Maps show power, and they confer power. They reflect the way those in power understand the world around them. This truth becomes evident when we consider a map of the United States, with its familiar rectilinear boundaries to the north and south and patchwork of state borders spanning the landmass. This map represents one viewpoint: that of the colonizer. And its current depictions suppress the viewpoints and realities of the thousands of tribes who first inhabited this continent and continue to call this land home.

The Native Land map subverts the colonist map, taking those same geographic images of landmasses with which we are so familiar and painting them with entirely different colors—quite literally.

“We understand that we can’t own land,” McRae says of Indigenous peoples. “We are in relation with the land. I’m not just seeing my yard as a yard, but rather the trees that are in this shared space are relations. The soil under my feet, the plants that grow here, they are also my relations.”

Yet McRae acknowledges that she also lives in the Western world. “We either have to rent or own if we are so privileged to do so,” McRae says. “We must balance these two juxtaposed understandings.”

This contestation is manifested in the Native Land map. Western cartography blends with nebulous regions where tribes both lived and live, where languages were spoken and are spoken, and where Indigenous peoples and colonizers formed treaties. While most Western maps represent a certain point in time, Native Land maps represent many pre-colonized points in time. While Western maps provide strict boundaries of ownership, Native Land maps show fluid, overlapping regions for places tribes have called and currently call home.

How Native Land Digitally Created a Community-Based Map

As a settler born in traditional Katzie territory and raised in Okanagan lands, Temprano wanted to create an invitation to other settlers to learn about whose land they occupy and to start a deeper intellectual and emotional connection in the process. The purpose of the project has since evolved to providing an empowering place for Indigenous peoples to affirm and share their home territories, history.

While Temprano continues to spearhead the technological work, Native Land Digital is Indigenous-led. Native people from around the world comprise the board of directors. An advisory board of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous cartographers also supports the project, along with volunteers who constantly refine the map as they gain more information.

Most Native Land Digital work takes place on the unceded lands of the Musqueam, Tsleil-waututh, and Squamish Nations. The Coast Salish people, to whom these nations belong, have lived along the northwest coast of North America for over 10,000 years. You can learn more about their history by finding them on the map.

Initially, Temprano relied heavily on colonial knowledge to fill in the map. But as the purpose of the project metamorphosed, the sources of information have, too. Now Native Land Digital leans heavily on knowledge gathered from Indigenous communities themselves, via both direct communication and archival sources.

Building community and being in community with Indigenous peoples are at the heart of making this map. McRae says it involves conversations with Native communities, guided by elders, who help to work through each individual situation.

“This map is a platform for Indigenous people to tell stories,” McRae says. “It goes back to being community based. If a community has a story it wants to share that will help us represent them on their own terms in the map, we’re happy to follow the lead of the community.”

Filling in each inch of the map requires gaining local knowledge from each place, in addition to contending with a stream of other considerations, such as Indigenous data sovereignty.

“Some knowledge is sacred—it doesn’t go out into the general world,” McRae says. “There are stories that remain within the community only. It all depends on community, and permissions to share, and so on. We just provide the platform for those who want to share their stories with the world.”

Native Land Digital deals with each situation uniquely and with as much care and empathy as required.

“The deeper history and understandings of Turtle Island (the native term for North America) and other parts of the world differ greatly, depending on which region of the world you’re from,” McRae explains. “And so we look to regional expertise and we promote that knowledge rather than our own projected understandings of what that colonial history or that Indigenous history might be in other places, particularly those places where we’re not from.”

Why These Maps Remain Eternally Incomplete

Just as one map cannot represent one point in history, Native Land Digital’s maps are constantly refined over time. The site doesn’t currently offer a print version of a map, to ensure maps can continue to be updated as needed.

In fact, evolution is one of the tenets this project, as reflected in the disclaimer that pops up when you open the map:

“This map does not represent or intend to represent official or legal boundaries of any Indigenous nations. To learn about definitive boundaries, contact the nations in question. Also, this map is not perfect—it is a work in progress with tons of contributions from the community. Please send us fixes if you find errors.”

Embracing imperfection drives this form of storytelling. Gathering information for the map is a volunteer-led, crowdsourced process. It’s not bound by rigorous academic requirements. Think of it as an Indigenous Wikipedia of sorts, whereby information is communicated visually through the map. This allows Native Land Digital to be updated efficiently, yet McRae says that the site is extremely hesitant to ever declare a map to be entirely accurate.

Its principle map remains eternally incomplete. Currently, Native Land Digital does not contain information for some areas of the world. This is not because Indigenous peoples, territories, languages, and treaties do not exist on these lands. Rather, there is still work to be done. The “work in progress” moniker also signifies that Native Land Digital will update information as needed. It sometimes uses colonial naming practices. The board makes hard decisions regarding who belongs on the map and where, which inherently involves rejecting inaccurate or insufficient sources. Ultimately, this is a human process and mistakes get made, which have real-life consequences of hurting others.

The question of who gets to say who belongs on the map remains an open question.

“We make a very conscious effort to not dictate someone’s existence,” McRae says. “Maps have been used as a colonial tool to erase people off of land. We want to do the exact opposite. That ties back into why this project is community based. If anything’s missing, or if anything needs to be changed, we listen to a community and what their needs are so that they can represent themselves on the map.”

Reciprocity is important to Native Land Digital. Collecting information for mapping is reliant on community, and as an open-source platform, anyone can use the map’s information as long as they do so responsibly and ethically. In fact, McRae hopes that in the future her nonprofit can support Indigenous communities in their own mapping projects.

Moving Beyond Land Acknowledgements

The Native Land maps invite Indigenous peoples to share their stories and settlers to learn them. For adventurers, looking up and acknowledging whose land you’re on can be a logical first step to pay respect and discover more about a new place. McRae emphasizes that this is only the first of a lifelong journey to gain a deeper understanding and connection to the land. The next step, she says, is for map users to build a relationship with the nations on whose land they stand.

“Our hope is that the map is a starting point for conversation and to build relationships,” McRae says.

This intention is embedded into the map itself. Examine the three maps to see how they relate to each other and how they seemingly don’t. Focus on a particular area to get a clearer view of the tribes represented there. By clicking on a place, you can find links to the Indigenous nations who call that land home. From there you can learn a little of the local language, dive into history, and nurture the seeds of consciousness that the map plants in your mind.

In addition to learning about Indigenous peoples and their land, the Native Land map invites users to learn from the land itself. The Native Land Digital Teacher’s Guide asks users to consider the land as pedagogy, a form of learning:

“Looking at the land from an Indigenous perspective means understanding that the land is a living being. This understanding both gives us insight into and increases our awareness of how we treat and interact with the land. Indigenous people hold the land up as both a living being and as a teacher. ‘Living lightly’ on the land has always been emphasized as a means of minimizing environmental impact and ensuring a continued quality of life for future generations to come,” the guide puts forth.

For McRae, viewing the land as a relation is a kind of North Star as we adventure through places both new and familiar. She asks, “How must you behave to be in good relation to the land and also to the people whose land that you are on?”

This article was written and edited on the lands of the Ute, Cheyenne, and Arapaho peoples.

The post Who Decides What Goes on a Map? appeared first on Outside Online.

by Abigail Levene via Outside Online

Comments